This briefing note is prepared jointly by Garden Court Chambers and the Migrant and Refugee Children's Legal Unit to raise awareness in the sector of a sudden spike in the numbers of asylum claims by Albanian nationals which have been certified as 'clearly unfounded' under s.94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002, and to encourage a practical response that protects clients at risk of refoulement to Albania.

This note is prepared as a resource that we hope will save legal practitioners time in their daily practice. It is intended to be used by new-starters without too much supervision. Experienced legal practitioners in this field will already be aware of the issues faced by Albanian nationals whereby many have faced certification of their initial asylum claims, leaving them in uncertain fresh claim territory and exposing them to a risk of detention and removal, and/or of being exploited due to their lack of immigration status. If asylum claims are prepared more thoroughly at the initial stage, we hope that fewer will be certified in the future.

It is acknowledged that many legal practitioners in the sector will already have these tactics in mind, but that the purpose of this note is to ensure that as many practitioners as possible start considering preparing their cases in this way due to the spike in certification. It is hoped that the experienced caseworkers, solicitors and supervisors share their tactics and any useful tips from this paper and their own experience with their teams, particularly the more junior members.

Background

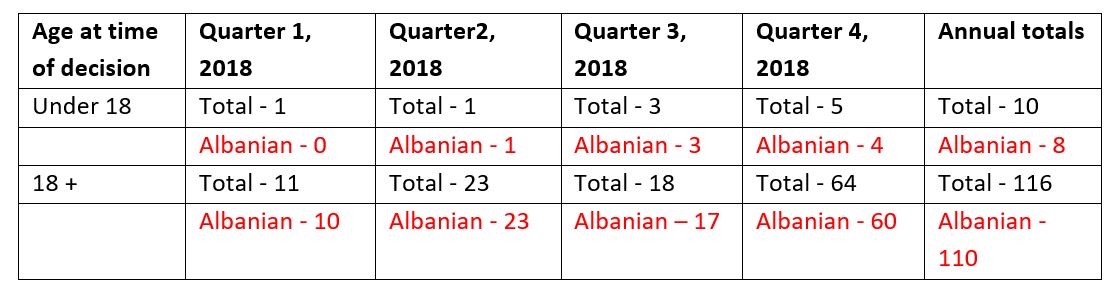

Asylum claims by Albanians are, increasingly, likely to be certified under section 94. The Home Office Country Policy and Information Notes (CPINs) on blood feuds [1], domestic abuse and violence against women [2], and sexual orientation and gender identity [3] all indicate that claims are likely to be certifiable as clearly unfounded, while the CPIN on people trafficking says that claims should be considered for certification [4]. The statistics suggest that this policy is being followed by caseworkers. Home Office figures illustrate that 93.6% of all certified refusals for unaccompanied asylum seeking children (UASCs) in the first three quarters of 2018, 118 out of 126, are Albanian. Albanian clients are thus at much higher risk of certification, in general, than clients of other nationalities.

Our experience is that many Albanian claimants are not challenging these certifications by judicial review, in many cases because they are not advised by their solicitors that they can or should do so. This paper is intended to help solicitors who are preparing Albanian asylum cases. In our view, it is essential to prepare these cases from the outset with the expectation that they may be certified, and to ensure that the necessary evidence to establish the claimant’s claim is put before the decision-maker at the initial decision stage.

Relevant law and procedure

Where an asylum claim is certified as “clearly unfounded” under section 94, the effect is that the claimant can only appeal after they have left the United Kingdom. Obviously, in an asylum case an out-of-country appeal is of little use, and so a claimant faced with a section 94 certification will in all probability want to challenge it by way of judicial review. Such judicial reviews are now normally dealt with by the Upper Tribunal.

A claim being “clearly unfounded” means “so clearly without substance that it was bound to fail”, Thangarasa and Yogathas [2002] UKHL 36. If any reasonable doubt exists as to whether the claim may succeed then it is not clearly unfounded, ZT (Kosovo) [2009] UKHL 6. In view of this, where a protection claim is certified as clearly unfounded, the certification normally is not based upon issues of credibility, unless the claim is so incredible that no one could believe it: see ZL and VL [2003] EWCA Civ 25. Rather, the certification is usually based on the decision-maker’s assessment that even if the claim is entirely true, the claimant could avail themselves of a sufficiency of protection from the authorities in their home country, and/or could safely and reasonably relocate internally to another part of their home country.

Unlike an appeal, a claim for judicial review is usually focused on the legality of the decision at the time it was taken, based on the evidence which was before the decision-maker at that time.

Therefore, from the claimant’s perspective, it is crucially important that the necessary evidence to establish their claim has been provided to the Secretary of State before the initial decision. This contrasts with the usual practice of legal aid lawyers. Typically the Legal Aid Agency does not fund expert reports until the appeal stage, and so it is not until the appeal that a solicitor is in a position to put forward their best case. Such an approach should not be taken in Albanian cases, where in most cases lawyers should expect that the claim is likely to be certified and that there will be no appeal stage. In short, those representing Albanians should prepare to put forward their best case at the initial decision stage, rather than waiting for the appeal.

What does this mean in practice?

There is now a strong risk that Albanian asylum claims (including those brought by children and survivors of trafficking) will be certified on the basis of sufficiency of protection and/or internal relocation. To a large extent these are questions of fact, for which evidence will be required.

Due to the nature of the funding available and the position taken by the Legal Aid Agency in relation to funding for expert evidence at the Legal Help stage we have seen a significant problem in challenging certification decisions since often the critical evidence – showing that an individual is at particular risk from a powerful gang, and/or showing that an individual is so vulnerable that it is unduly harsh for them to relocate internally – is simply not before the decision-maker at the time of certification. This makes it difficult to succeed in a judicial review claim.

Practitioners representing Albanian asylum claimants must now take steps to ensure that Albanian cases are 'Front Loaded' – meaning that evidence that might usually be obtained at appeal stage must be obtained and submitted at the initial pre-decision stage, given the strong likelihood that an asylum claimant from Albanian will not benefit from the opportunity to have their case considered on appeal, and in light of the need to ensure that the asylum claim that is before the Secretary of State is sufficiently evidenced to make an arguable case at Judicial Review stage.

What kind of evidence will be required?

One critically important type of evidence in Albanian asylum cases is medical evidence. In many cases, such evidence will be essential to success:

- In trafficking cases, the country guidance cases of TD and AD (Trafficked women) CG [2016] UKUT 92 (IAC) and AM and BM (Trafficked women) Albania CG [2010] UKUT 80 (IAC) – not just the headnotes but also the decisions in respect of the individual appellants, who were successful in their appeals – well illustrate that medical evidence of mental ill-health and vulnerability often plays an important role, in illustrating that a trafficking victim is vulnerable to re-trafficking and/or that it is unduly harsh to expect them to relocate internally. Although the March 2019 version of the Home Office CPIN claims that the situation has improved since TD and AD, it also acknowledges that each claim must be considered on its individual facts. In any case, a hypothetical tribunal would have to take the country guidance as a starting point. Thus, for a trafficking victim, evidence of mental ill-health and vulnerability is likely to be critically important to success in their asylum claim. Although the country guidance relates to women, boys and men can also be victims of trafficking and can also experience mental ill-health and vulnerability, and much of the country guidance is in practice applicable to them.

- In blood feud cases, it may well be possible for a claimant to establish that they face a risk of blood feud in their home area for which the state does not afford adequate protection, especially if they come from a conservative rural area in the north of Albania. The CPIN is not satisfactory on this point, as set out at length in an April 2019 paper by David Neale of Garden Court (Albanian blood feuds and certification: a critical view). But in many cases they will still need to show that it is unduly harsh for them to relocate internally to avoid the risk, and in this context medical evidence may play a major role.

- Likewise, in domestic violence cases, medical evidence may play a critically important role. In domestic violence cases the Home Office asserts that there is a general sufficiency of protection, following DM (Sufficiency of Protection, PSG, Women, Domestic Violence) Albania CG [2004] UKIAT 00059. But that case concerned a woman who faced threats of violence from her ex-boyfriend. On a cultural level, that scenario may well be distinguishable from a situation where a person fears their father, husband or another family member. The Upper Tribunal accepted in AM and BM at [182] that there is little evidence that the state would intervene, especially in the north, if a trafficking victim is at risk of violence from her family or her husband. There is no reason why the same would not be true of a person who has not been trafficked but who has offended against their family’s honour for some other reason. In such a scenario, however, a claimant who can establish a risk in their home area will still need to show that it is unduly harsh for them to relocate to another part of Albania away from their family – and medical evidence will, again, be highly relevant to that question.

- Finally, in gay and lesbian cases, the route to success in light of BF (Tirana - gay men) Albania CG [2019] UKUT 93 (IAC) is likely to turn on establishing that it would be unduly harsh for a person at risk in their home area to relocate to Tirana based on their individual circumstances, because mental and/or physical ill-health and/or other vulnerabilities means that such relocation would be particularly harsh for them. Again, self-evidently, such an argument requires medical evidence.

Lawyers should be alert to possible mental ill-health in every case, and should never assume that a claimant is not mentally ill merely because they have not sought help of their own volition or because they “seem fine”. This is particularly important when working with asylum-seeking children and young adults. It is known that asylum-seeking children are at much higher risk than other children of developing mental health problems such as PTSD, and that these problems are not always detected. Given-Wilson et al (2016) state:

“Asylum seeking minors have heightened risk of developing mental health problems due to the stressors they have been exposed to in their home country (i.e. war, disruption to community life, witnessing deaths), in transit (i.e. sexual exploitation, separation from caregivers, illness) and upon arrival (i.e. uncertainty of refugee status, discrimination, low social support) (Derluyn & Broekaert, 2008; Fazel, Reed, Panter-Brick, & Stein, 2012). In addition a sustained lack of any parental figure further increases these young peoples’ vulnerability to mental health problems (Hodes et al., 2008). For example, one study suggests that unaccompanied minors are five times more likely to have emotional difficulties than those who are accompanied by a caregiver (Derluyn, Broekaert, & Schuyten, 2008)…

A review found that PTSD was ten times higher amongst asylum seeking youth than non-asylum seeking peers and prevalence of depression ranges from 5-30% and anxiety 10-30%, again higher in less settled populations (Fazel et al., 2014). However, often these adolescents’ difficulties are not detected due to lack of access to treatment, reluctance to seek help due to stigma or believing it would not help, or reporting somatic rather than psychological symptoms (Dura-Vila, Klasen, Makatini, Rahimi, & Hodes, 2012).” [5]

In our experience, it is commonplace that asylum-seeking children and young adults do not recognise their own mental health problems or seek help for them; cultural factors may play a role in this.

It is not acceptable for lawyers to put the onus on their client to raise any mental health problems. Rather, lawyers should proactively investigate these issues themselves, and make a referral for a medico-legal report where this is merited. If the claimant is engaged with support organisations such as Shpresa, or has a supportive and engaged foster carer or social worker, these can provide an invaluable source of information (provided of course that the claimant consents to such discussions taking place) from those who know the claimant better than their lawyer does.

In some cases, country expert evidence is also essential. For example, in many trafficking and/or blood feud cases the aggressor is a criminal gang and it is important to show their influence and reach – some criminal gangs in Albania have a national or even international reach, with drug trafficking operations in other European countries, and significant influence over the authorities.

Likewise, the culture of the client’s home area may be critically important to the claim – in a conservative northern village attitudes to domestic violence, LGBT people, unmarried mothers etc may be much more hostile than they would be in Tirana. Country expert evidence can be very helpful in shedding light on the situation in a local area. Lawyers should always be conscious that country expert evidence is rigorously scrutinised by the Tribunal. In MS (Trafficking - Tribunal's Powers - Art. 4 ECHR) Pakistan [2016] UKUT 226 (IAC), the Upper Tribunal considered that those instructing expert witnesses should ensure that the expert is provided with a copy of MOJ and Others (Return to Mogadishu) Somalia CG [2014] UKUT 442 (IAC), at [23] - [27], where the Upper Tribunal detailed the duties of expert witnesses. The Upper Tribunal also considered that ‘each expert's report should, in turn, make clear that these passages have been received and read by the mechanism of a simple declaration to this effect.’

What else will be required?

It is likely to be necessary to take a detailed statement from your client which covers their basis of claim, and addresses all of the relevant issues in relation to sufficiency of protection, obstacles to internal relocation, and any vulnerabilities or family issues which may be relevant. Whether or not this witness statement is submitted to the Home Office, it will be vital to identifying the issues in the case for which evidence is required.

Practitioners will also need to be prepared to draft detailed legal submissions which address the relevant issues, refer to any evidence obtained, and effectively argue the case that would be placed before the Tribunal in Judicial Review proceedings. These should ideally be submitted in the five working day period for further submissions after the full asylum interview takes place, unless the particular circumstances of the case means that earlier submission would be in the client’s best interests.

How will practitioners obtain funding for this?

Through our experience of working with grassroots Albanian organisation Shpresa, it is clear that Albanian asylum cases are frequently subject to delay which is longer than that experienced by claimants from other countries. It is therefore likely that, if the situation remains static, there will be sufficient time between the initial lodging of the asylum claim and any decision for expert evidence to be obtained, including the need to seek authority from the LAA if relevant.

As practitioners ourselves we are aware of the reluctance of the Legal Aid Agency to authorise funding to obtain expert evidence at the Legal Help stage, the usual rationale being that the Home Office may accept the case, or accept it in part, and in that the Reasons for Refusal Letter will narrow the issues in the case such that it is clearer what, if any, expert evidence is required.

It is therefore clear that practitioners wishing to 'front load' Albanian asylum claims will need to be prepared to argue their case with the Legal Aid Agency and that applications for Controlled Work extensions will need to be clearly and cogently argued by reference to the data referred to in this paper, and the risk to their particular client.

A well-drafted extension request is much more likely to be granted, than a brief request that does not explain why the case should be treated differently from the norm, nor make the case for the specific disbursement request by reference to the client's case.

Practitioners may wish to draft a template submission setting out the reasons why it is likely to be necessary to obtain expert evidence, with standard sections addressing the high risk of certification of Albanian cases, and tailored sections that refer to the facts specific to their client. Those representing a high volume of Albanian nationals are likely to find this of particular use.

We would suggest that extension requests address the following:

- The likelihood that the case will be certified (both on the basis of the nationality of the claimant/Home Office policy, and by reference to specific aspects of the case)

- The gaps in the evidence that is in the public domain/efforts to obtain evidence in relation to specific issues raised in the case (e.g. the influence and reach of a particular criminal gang)

- The flaws in the current evidence that the Home Office is likely to rely on in deciding the claim

- The extent to which expert evidence has the potential to cure the defects in the evidence in the public domain

- The extent to which medical evidence is necessary to the assessment of vulnerability for the purposes of a) internal relocation and b) the application off relevant case law

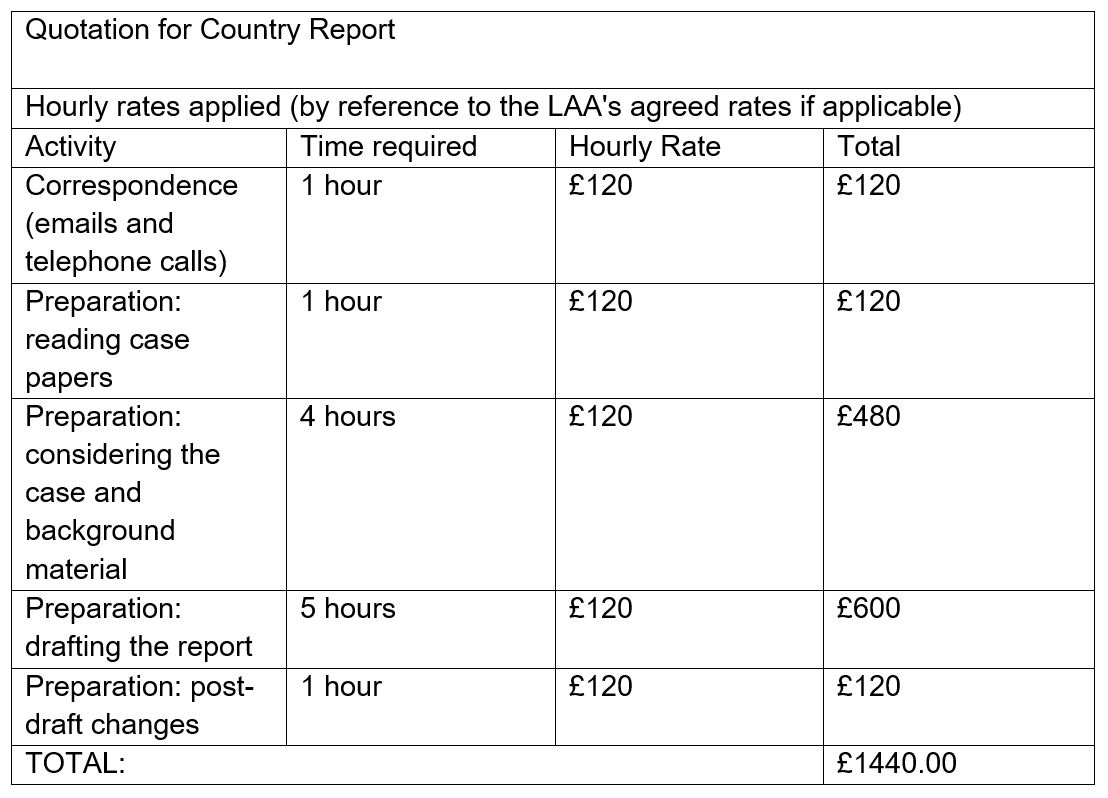

Practitioners should be preparing the initial funding applications in a detailed and thorough way. We know that the LAA want to see 3 alternative quotes for each expert and a complete breakdown of all work required so lawyers should ensure their request to each expert asks for this as well as a full copy of the CV. Just a simple “my report will be £1000” will not pass with the LAA – they want to know the hourly rate and as precisely as possible, how many hours will be spent on each activity. For example:

In relation to obtaining expert medical evidence we would advise that it is likely to be necessary to ensure that your client has seen a GP or other healthcare professional competent to diagnose any particular health difficulty. It will be easier to obtain funding for a medical report if there a written diagnosis.

If your client has been seeing a counsellor/psychologist through their GP/college/other location, then it may be necessary to write to that person or organisation before making the application asking if they would be prepared to write a report addressing the issues on which you are planning to instruct an independent psychiatrist/psychologist. In our experience the LAA is more likely to be willing to incur the costs of obtaining a report from the person who is treating your client and may refuse requests for independent experts on the basis that the treating healthcare professional is a more appropriate person to provide this evidence. It will therefore be necessary to provide evidence either that the treating healthcare professional is unable to provide a report (preferably by letter or email), or that the healthcare professional is not sufficiently qualified to provide the type of evidence that will be given weight by the Home Office (e.g. because they are not able/qualified to diagnose psychiatric disorders).

We would recommend that practitioners identify their preferred choice of expert and attach the other quotes as a comparison. Where you intend to instruct a claimant’s treating healthcare professional, there is likely to be less need to provide alternative quotes provided that you make clear that the person you wish to instruct is the treating physician. Where your preferred expert’s total quote is higher than that provided by comparators, it is essential that you make a detailed and reasoned argument as to why, in your professional opinion, your first choice expert is the most appropriate to instruct.

We would further recommend that every extension application should be sent with detailed submissions (as suggested above) typed separately and attached to the form. The forms themselves are only 2-3 pages long and there isn’t enough space to detail the reasons why the report is required to the level required to persuade the LAA to agree funding in these circumstances.

In addition to addressing the risk of certification, submissions will have the best prospect of persuading the LAA to grant funding where they cover the following issues:

- Background history

- Analysis of merits of the case (including any legal submissions and reference to cases/CG/CPIN’s/other literature)

- Details of how much has been carried out and how much of the disbursement limit has been used

- Full details of the preferred experts including a detailed explanation why this report is so crucial at this stage pre-decision (this is really important where you are instructing an expert who is more costly than the comparable quotes)

- Details of any further work required on the file including other disbursements (i.e. interpreters/translations)

- Any details as to why the application should be considered urgently outside of the LAA’s usual timeframe which is approx. three weeks

The most persuasive way to get the LAA to fund reports is to show that the funding application engages the facts of that particular case as well as referencing to the external information about risk of certification.

We believe that although there is a risk that the LAA may initially refuse to grant the extension due to lack of awareness of the impact of certification, practitioners should not simply accept an initial refusal to fund, and should re-submit their request. It may be necessary to seek Counsel's advice pro bono to persuade the LAA that refusal to fund front-loading of asylum claims by clients at a high risk of certification should be reversed.

We would invite legal practitioners to use parts of this note in their extension applications if it helps them with the specific issues of their case; however, we specifically ask that practitioners do not send the whole paper to the LAA in support of an application for an extension.

Links to relevant guidance:

- 2018 Standard Civil Contract Specification

Section 4: Payment for controlled work

This details payment for “Escape Fee” cases at the Legal Help Stage where you are paid a standard fee of £413.00 for the Legal Help, but if you incur work on the file which goes 3 x over the standard amount the fee on this file can be claimed as an escape fee; and in theory you can be paid the whole amount for your preparation of the case. However, prior authority is still required for incurring disbursement costs over the £400.00 limit and you would still need to submit your funding extension application to the Legal Aid Agency.

- Standard Civil Contract Payment Annex Oct 2011

Section 4 & Section 7

This details the hourly rates for funding at both Legal Help and Controlled Work Stage. The Legal Help stage covers the work we carry out at the initial stage, i.e. Asylum claim / Further Submissions up to a decision from the Home Office. Controlled Work covers the stage following a negative decision from the Home Office, for example, the asylum appeal.

- CW3 Funding Extension Application Forms & Checklists

This is a link to the paper and electronic forms for requesting an extension of costs/increase to the disbursement limit. The checklists are particularly helpful to go over prior to submitting the funding request.

David Neale is a legal researcher and former barrister at Garden Court Chambers.

Gurpinder Khanba is the Breaking the Chains Project Caseworker Supervisor for MiCLU at Inslington Law Centre

Footnotes

[1] Home Office Country Policy and Information Note, “Albania: Blood feuds,” October 2018 at 2.7

[2] Home Office Country Policy and Information Note, “Albania: Domestic abuse and violence against women,” December 2018 at 2.6

[3] Home Office Country Policy and Information Note, “Albania: Sexual orientation and gender identity,” April 2019 at 2.6

[4] Home Office Country Policy and Information Note, “Albania: People trafficking,” March 2019 at 2.6

[5] Given-Wilson, Z., Herlihy, J. and Hodes, M. (2016) “Telling the story: A psychological review on assessing adolescents’ asylum claims,” Canadian Psychology Special Edition: Refugee